Introduction to Bayesian Analysis Procedures

Assessing Markov Chain Convergence

Simulation-based Bayesian inference requires using simulated draws to summarize the posterior distribution or calculate any relevant quantities of interest. You need to treat the simulation draws with care. There are usually two issues. First, you have to decide whether the Markov chain has reached its stationary, or the desired posterior, distribution. Second, you have to determine the number of iterations to keep after the Markov chain has reached stationarity. Convergence diagnostics help to resolve these issues. Note that many diagnostic tools are designed to verify a necessary but not sufficient condition for convergence. There are no conclusive tests that can tell you when the Markov chain has converged to its stationary distribution. You should proceed with caution. Also, note that you should check the convergence of all parameters, and not just those of interest, before proceeding to make any inference. With some models, certain parameters can appear to have very good convergence behavior, but that could be misleading due to the slow convergence of other parameters. If some of the parameters have bad mixing, you cannot get accurate posterior inference for parameters that appear to have good mixing. See Cowles and Carlin (1996) and Brooks and Roberts (1998) for discussions about convergence diagnostics.

Visual Analysis via Trace Plots

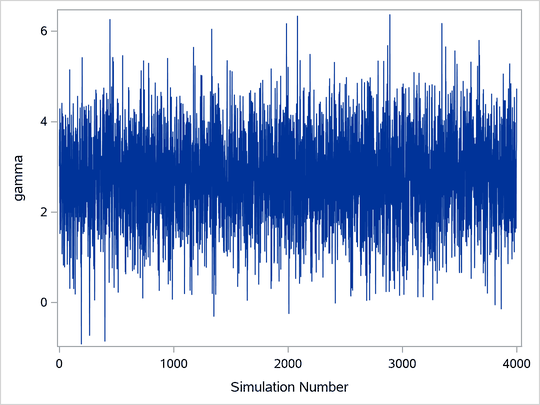

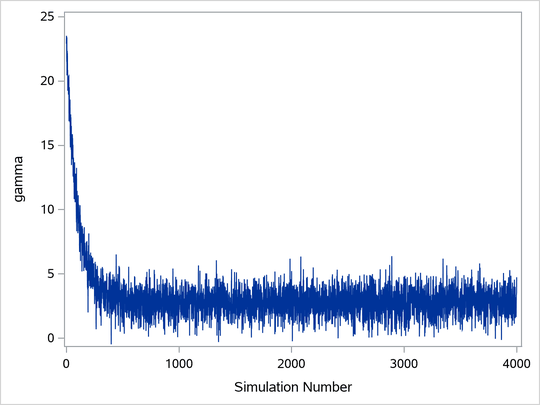

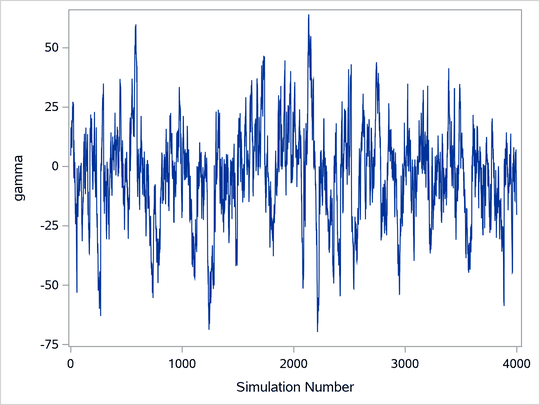

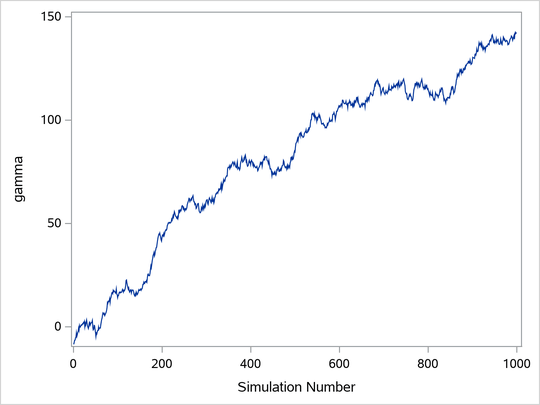

Trace plots of samples versus the simulation index can be very useful in assessing convergence. The trace tells you if the chain has not yet converged to its stationary distribution—that is, if it needs a longer burn-in period. A trace can also tell you whether the chain is mixing well. A chain might have reached stationarity if the distribution of points is not changing as the chain progresses. The aspects of stationarity that are most recognizable from a trace plot are a relatively constant mean and variance. A chain that mixes well traverses its posterior space rapidly, and it can jump from one remote region of the posterior to another in relatively few steps. Figure 1 through Figure 4 display some typical features that you might see in trace plots. The traces are for a parameter called .

Figure 1 displays a "perfect" trace plot. Note that the center of the chain appears to be around the value 3, with very small fluctuations. This indicates that the chain could have reached the right distribution. The chain is mixing well; it is exploring the distribution by traversing to areas where its density is very low. You can conclude that the mixing is quite good here.

Figure 2 displays a trace plot for a chain that starts at a very remote initial value and makes its way to the targeting distribution. The first few hundred observations should be discarded. This chain appears to be mixing very well locally. It travels relatively quickly to the target distribution, reaching it in a few hundred iterations. If you have a chain that looks like this, you would want to increase the burn-in sample size. If you need to use this sample to make inferences, you would want to use only the samples toward the end of the chain.

Figure 3 demonstrates marginal mixing. The chain is taking only small steps and does not traverse its distribution quickly. This type of trace plot is typically associated with high autocorrelation among the samples. To obtain a few thousand independent samples, you need to run the chain for much longer.

The trace plot shown in Figure 4 depicts a chain with serious problems. It is mixing very slowly, and it offers no evidence of convergence. You would want to try to improve the mixing of this chain. For example, you might consider reparameterizing your model on the log scale. Run the Markov chain for a long time to see where it goes. This type of chain is entirely unsuitable for making parameter inferences.

Statistical Diagnostic Tests

The Bayesian procedures include several statistical diagnostic tests that can help you assess Markov chain convergence. For a detailed description of each of the diagnostic tests, see the following subsections. Table 1 provides a summary of the diagnostic tests and their interpretations.

Table 1: Convergence Diagnostic Tests Available in the Bayesian Procedures

Gelman and Rubin Diagnostics

Gelman and Rubin diagnostics (Gelman and Rubin 1992; Brooks and Gelman 1997) are based on analyzing multiple simulated MCMC chains by comparing the variances within each chain and the variance between chains. Large deviation between these two variances indicates nonconvergence.

Define , where

, to be the collection of a single Markov chain output. The parameter

is the tth sample of the Markov chain. For notational simplicity,

is assumed to be single dimensional in this section.

Suppose you have M parallel MCMC chains that were initialized from various parts of the target distribution. Each chain is of length n (after discarding the burn-in). For each , the simulations are labeled as

and

. The between-chain variance B and the within-chain variance W are calculated as

The posterior marginal variance, , is a weighted average of W and B. The estimate of the variance is

If all M chains have reached the target distribution, this posterior variance estimate should be very close to the within-chain variance W. Therefore, you would expect to see the ratio be close to 1. The square root of this ratio is referred to as the potential scale reduction factor (PSRF). A large PSRF indicates that the between-chain variance is substantially greater than the within-chain variance, so that longer simulation is needed. If the PSRF is close to 1, you can conclude that each of the M chains has stabilized, and they are likely to have reached the target distribution.

A refined version of PSRF is calculated, as suggested by Brooks and Gelman (1997), as

where

and

All the Bayesian procedures also produce an upper confidence limit of

. Gelman and Rubin (1992) showed that the ratio

in

has an F distribution with degrees of freedom

and

. Because you are concerned only if the scale is large, not small, only the upper

confidence limit is reported. This is written as

In the Bayesian procedures, you can specify the number of chains that you want to run. Typically three chains are sufficient. The first chain is used for posterior inference, such as mean and standard deviation; the other chains are used for computing the diagnostics and are discarded afterward. This test can be computationally costly, because it prolongs the simulation M-fold.

It is best to choose different initial values for all M chains. The initial values should be as dispersed from each other as possible so that the Markov chains can fully explore different parts of the distribution before they converge to the target. Similar initial values can be risky because all of the chains can get stuck in a local maximum; that is something this convergence test cannot detect. If you do not supply initial values for all the different chains, the procedures generate them for you.

Geweke Diagnostics

The Geweke test (Geweke 1992) compares values in the early part of the Markov chain to those in the latter part of the chain in order to detect failure of convergence. The statistic is constructed as follows. Two subsequences of the Markov chain are taken out, with

and

, where

. Let

, and define

Let and

denote consistent spectral density estimates at zero frequency (see the subsection Spectral Density Estimate at Zero Frequency for estimation details) for the two MCMC chains, respectively. If the ratios

and

are fixed,

, and the chain is stationary, then the following statistic converges to a standard normal distribution as

:

This is a two-sided test, and large absolute z-scores indicate rejection.

Spectral Density Estimate at Zero Frequency

For one sequence of the Markov chain , the relationship between the h-lag covariance sequence of a time series and the spectral density, f, is

where i indicates that is the complex argument. Inverting this Fourier integral,

It follows that

which gives an autocorrelation adjusted estimate of the variance. In this equation, is the naive variance estimate of the sequence

and

is the lag h autocorrelation. Due to obvious computational difficulties, such as calculation of autocorrelation at infinity, you cannot effectively estimate

by using the preceding formula. The usual route is to first obtain the periodogram

of the sequence, and then estimate

by smoothing the estimated periodogram. The periodogram is defined to be

The procedures use the following way to estimate from p (Heidelberger and Welch 1981). In

, let

and

.[3] A smooth spectral density in the domain of

is obtained by fitting a gamma model with the log link function, using

as response and

as the only regressor. The predicted value

is given by

where and

are the estimates of the intercept and slope parameters, respectively.

Heidelberger and Welch Diagnostics

The Heidelberger and Welch test (Heidelberger and Welch 1981, 1983) consists of two parts: a stationary portion test and a half-width test. The stationarity test assesses the stationarity of a Markov chain by testing the hypothesis that the chain comes from a covariance stationary process. The half-width test checks whether the Markov chain sample size is adequate to estimate the mean values accurately.

Given , set

,

, and

. You can construct the following sequence with s coordinates on values from

:

where is the rounding operator, and

is an estimate of the spectral density at zero frequency that uses the second half of the sequence (see the section Spectral Density Estimate at Zero Frequency for estimation details). For large n,

converges in distribution to a Brownian bridge (Billingsley 1986). So you can construct a test statistic by using

. The statistic used in these procedures is the Cramer–von Mises statistic[4]; that is

. As

, the statistic converges in distribution to a standard Cramer–von Mises distribution. The integral

is numerically approximated using Simpson’s rule.

Let , where

, and

. If n is even, let

; otherwise, let

. The Simpson’s approximation to the integral is

Note that Simpson’s rule requires an even number of intervals. When n is odd, is set to be 0 and the value does not contribute to the approximation.

This test can be performed repeatedly on the same chain, and it helps you identify a time t when the chain has reached stationarity. The whole chain, , is first used to construct the Cramer–von Mises statistic. If it passes the test, you can conclude that the entire chain is stationary. If it fails the test, you drop the initial

of the chain and redo the test by using the remaining

. This process is repeated until either a time t is selected or it reaches a point where there are not enough data remaining to construct a confidence interval (the cutoff proportion is set to be

).

The part of the chain that is deemed stationary is put through a half-width test, which reports whether the sample size is adequate to meet certain accuracy requirements for the mean estimates. Running the simulation less than this length of time would not meet the requirement, while running it longer would not provide any additional information that is needed. The statistic calculated here is the relative half-width (RHW) of the confidence interval. The RHW for a confidence interval of level is

where is the z-score of the

th percentile (for example,

if

),

is the variance of the chain estimated using the spectral density method (see explanation in the section Spectral Density Estimate at Zero Frequency), n is the length, and

is the estimated mean. The RHW quantifies accuracy of the

level confidence interval of the mean estimate by measuring the ratio between the sample standard error of the mean and the mean itself. In other words, you can stop the Markov chain if the variability of the mean stabilizes with respect to the mean. An implicit assumption is that large means are often accompanied by large variances. If this assumption is not met, then this test can produce false rejections (such as a small mean around 0 and large standard deviation) or false acceptance (such as a very large mean with relative small variance). As with any other convergence diagnostics, you might want to exercise caution in interpreting the results.

The stationarity test is one-sided; rejection occurs when the p-value is greater than . To perform the half-width test, you need to select an

level (the default of which is 0.05) and a predetermined tolerance value

(the default of which is 0.1). If the calculated RHW is greater than

, you conclude that there are not enough data to accurately estimate the mean with

confidence under tolerance of

.

Raftery and Lewis Diagnostics

If your interest lies in posterior percentiles, you want a diagnostic test that evaluates the accuracy of the estimated percentiles. The Raftery-Lewis test (Raftery and Lewis 1992, 1995) is designed for this purpose. Notation and deductions here closely resemble those in Raftery and Lewis (1995).

Suppose you are interested in a quantity such that

, where q can be an arbitrary cumulative probability, such as 0.025. This

can be empirically estimated by finding the 100nqth number of the sorted

. Let

denote the estimand, which corresponds to an estimated probability

. Because the simulated posterior distribution converges to the true distribution as the simulation sample size grows,

can achieve any degree of accuracy if the simulator is run for a very long time. However, running too long a simulation can be wasteful. Alternatively, you can use coverage probability to measure accuracy and stop the chain when a certain accuracy is reached.

A stopping criterion is reached when the estimated probability is within of the true cumulative probability q, with probability s, such as

. For example, suppose you want the coverage probability s to be 0.95 and the amount of tolerance r to be 0.005. This corresponds to requiring that the estimate of the cumulative distribution function of the 2.5th percentile be estimated to within

percentage points with probability 0.95.

The Raftery-Lewis diagnostics test finds the number of iterations, M, that need to be discarded (burn-ins) and the number of iterations needed, N, to achieve a desired precision. Given a predefined cumulative probability q, these procedures first find , and then they construct a binary

process

by setting

if

and 0 otherwise for all t. The sequence

is itself not a Markov chain, but you can construct a subsequence of

that is approximately Markovian if it is sufficiently k-thinned. When k becomes reasonably large,

starts to behave like a Markov chain.

Next, the procedures find this thinning parameter k. The number k is estimated by comparing the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) between two Markov models: a first-order and a second-order Markov model. A jth-order Markov model is one in which the current value of depends on the previous j values. For example, in a second-order Markov model,

where . Given

, you can construct two transition count matrices for a second-order Markov model:

For each k, the procedures calculate the BIC that compares the two Markov models. The BIC is based on a likelihood ratio test statistic that is defined as

where is the expected cell count of

under the null model, the first-order Markov model, where the assumption

holds. The formula for the expected cell count is

The BIC is , where

is the k-thinned sample size (every kth sample starting with the first), with the last two data points discarded due to the construction of the second-order Markov model. The thinning parameter k is the smallest k for which the BIC is negative. When k is found, you can estimate a transition probability matrix between state 0 and state 1 for

:

Because is a Markov chain, its equilibrium distribution exists and is estimated by

where and

. The goal is to find an iteration number m such that after m steps, the estimated transition probability

is within

of equilibrium

for

. Let

and

. The estimated transition probability after step m is

which holds when

Therefore, by time m, is sufficiently close to its equilibrium distribution, and you know that a total size of

should be discarded as the burn-in.

Next, the procedures estimate N, the number of simulations needed to achieve desired accuracy on percentile estimation. The estimate of is

. For large n,

is normally distributed with mean q, the true cumulative probability, and variance

By using similar reasoning, the procedures first calculate the minimal number of iterations needed to achieve the desired accuracy, assuming the samples are independent:

If does not have that required sample size, the Raftery-Lewis test is not carried out. If you still want to carry out the test, increase the number of Markov chain iterations.

The ratio is sometimes referred to as the dependence factor. It measures deviation from posterior sample independence: the closer it is to 1, the less correlated are the samples. There are a few things to keep in mind when you use this test. This diagnostic tool is specifically designed for the percentile of interest and does not provide information about convergence of the chain as a whole (Brooks and Roberts 1999). In addition, the test can be very sensitive to small changes. Both N and

are inversely proportional to

, so you can expect to see large variations in these numbers with small changes to input variables, such as the desired coverage probability or the cumulative probability of interest. Last, the time until convergence for a parameter can differ substantially for different cumulative probabilities.

Autocorrelations

The sample autocorrelation of lag h for a parameter is defined in terms of the sample autocovariance function:

The sample autocovariance function of lag h of is defined by

Effective Sample Size

You can use autocorrelation and trace plots to examine the mixing of a Markov chain. A closely related measure of mixing is the effective sample size (ESS) (Kass et al. 1998).

where n is the total sample size and is the autocorrelation of lag k for

. The quantity

is referred to as the autocorrelation time. To estimate

, the Bayesian procedures first find a cutoff point k after which the autocorrelations are very close to zero, and then sum all the

up to that point. The cutoff point k is such that

, where

is the estimated standard deviation:

ESS and are inversely proportional to each other, and low ESS or high

indicates bad mixing of the Markov chain.